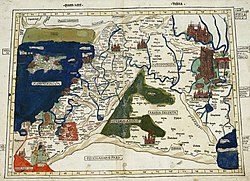

Plodni polumesec

Plodni polumesec se nalazi u jugozapadnoj Aziji i severoistočnoj Africi, a sastoji se od plodnih podregiona Mesopotamije i Levanta.[1][2] Kroz ovaj region protiču četiri velike reke: Nil, Jordan, Eufrat i Tigar. S južne strane je omeđen Sirijskom pustinjom a sa severne Anadolijom. Proteže se od istočne obale Sredozemnog mora do Persijskog zaliva zahvatajući teritoriju površine između 400.000 i 500.000 km². Zbog bogatog istorijskog nasleđa ovo područje se često naziva kolevkom civilizacije[3] i smatra se mestom nastanka pismenosti i otkrića točka.

Naziv Plodni polumesec je skovao američki arheolog Džejms Henri Brested (engl. James Henry Breasted) sa Univerziteta u Čikagu inspirisan činjenicom da je reč o plodnoj teritoriji čiji oblik podseća na polumesec. Ovovremene države čije se teritorije nalaze sasvim ili jednim delom unutar Plodnog polumeseca su Irak, Izrael (sa Palestinom), Jordan, Liban, Sirija, deo severoistočnog Egipta i mali deo jugozapadne Turske kao i zapadnog Irana.

Smatra se da je Plodni polumesec prva regija u kojoj se pojavila poljoprivreda kada su ljudi započeli proces čišćenja i modifikacije prirodne vegetacije kako bi uzgajali novopripitomljene biljke kao useve. Kao rezultat toga, rane ljudske civilizacije kao što je Sumer u Mesopotamiji doživele su procvat.[4] Tehnološki napredak u regionu uključuje razvoj poljoprivrede i upotrebu navodnjavanja.

Terminologija

urediTermin „Plodni polumesec“ popularizovao je arheolog Džejms Henri Brested u delima Osnove evropske istorije (1914) i Antička vremena, istorija ranog sveta(1916).[5][6][7][8][9][10] On je napisao:[5]

On leži kao vojska okrenuta prema jugu, sa jednim krilom koji se proteže duž istočne obale Sredozemnog mora, a drugim seže do Persijskog zaliva, dok je centar okrenut leđima severnim planinama. Kraj zapadnog krila je Palestina; Asirija čini veliki deo centra; dok je kraj istočnog krila Vavilonija. [...] Ovaj veliki polukrug, zbog nedostatka imena, može se nazvati Plodni polumesec.

U antici ne postoji jedinstveni termin za ovaj region. U vreme kada je Brested pisao, to je otprilike odgovaralo teritorijama Otomanskog carstva koje su ustupljene Britaniji i Francuskoj u Sporazumu Sajks-Pikota. Istoričar Tomas Šefler je primetio da je Brested pratio trend u zapadnoj geografiji da „prebriše klasične geografske razlike između kontinenata, zemalja i predela velikim, apstraktnim prostorima“, povlačeći paralele sa radom Halforda Makindera, koji je konceptualizovao Evroaziju kao 'stožer', područje“ okruženo 'unutrašnjim polumesecom', Bliskim istokom Alfreda Tajera Mahana i Mitteleuropa Fridriha Naumana.[11]

Biodiverzitet i klima

urediPlodni polumesec je imao mnogo različitih klima, a velike klimatske promene podstakle su evoluciju mnogih jednogodišnjih biljaka tipa „r“, koje daju više jestivog semena od višegodišnjih biljaka tipa „K“. Dramatična raznolikost u nadmorskoj visini u regionu dovela je do mnogih vrsta jestivih biljaka za rane eksperimente u uzgoju. Ono što je najvažnije, Plodni polumesec je bio dom osam neolitskih osnivačkih useva važnih u ranoj poljoprivredi (to su divlji preci emer pšenice, limca, ječma, lana, leblebije, graška, sočiva, gorke grahorice) i četiri od pet najvažnijih vrste domaćih životinja — krave, koze, ovce i svinje; u blizini je živela peta vrsta, konj.[12] Flora plodnog polumeseca obuhvata visok procenat biljaka koje mogu da se samooprašuju, ali mogu biti i unakrsno oprašivane.[12] Ove biljke, nazvane „selferi“, bile su jedna od geografskih prednosti ovog područja, jer nisu zavisile od drugih biljaka za reprodukciju.[12]

Istorija

urediPored toga što poseduje mnoga nalazišta sa skeletalnim i kulturnim ostacima predmodernih i ranih modernih ljudi (npr. u pećinama Tabun i Es Skul u Izraelu), kasnijih pleistocenskih lovaca-sakupljača i epipaleolitskih polusedentarnih lovaca-sakupljača (npr. Natufijani), plodni polumesec je najpoznatiji po svojim lokalitetima vezanim za poreklo poljoprivrede. Zapadna zona oko reka Jordana i gornjeg Eufrata dovela je do prvih poznatih neolitskih zemljoradničkih naselja (koji se nazivaju predgnčarski neolit A (PPNA), koji datiraju od oko 9.000 godina pre nove ere i uključuju veoma drevna nalazišta kao što su Gobekli Tepe, Čoga Golan i Džerihon (Tel es-Sultan).

Ovaj region, pored Mesopotamije (na grčkom znači „između reka“, između reka Tigra i Eufrata, leži na istoku Plodnog polumeseca), takođe je doživeo pojavu ranih složenih društava tokom sledećeg bronzanog doba. Takođe postoje rani dokazi iz regiona o pisanju i formiranje hijerarhijskih društava na državnom nivou. Ovo je regionu donelo nadimak „kolevka civilizacije”.

U ovom kraju su se prve biblioteke pojavile pre oko 4.500 godina. Najstarije poznate biblioteke nalaze se u Nipuru (u Sumeru) i Ebli (u Siriji), obe od oko 2500. p. n. e..[13]

Tigris i Eufrat izviru u planinama Taurus današnje Turske. Poljoprivrednici u južnoj Mesopotamiji morali su svake godine da zaštite svoja polja od poplava. Severna Mesopotamija je imala dovoljno kiše da omogući poljoprivredu. Za zaštitu od poplava pravili su nasipe.[14]

Rana pripitomljavanja

urediPraistorijske smokve bez semena otkrivene su u Gilgalu I u dolini Jordana, što sugeriše da su stabla smokava sađena pre nekih 11.400 godina.[15] Žitarice su se uzgajale u Siriji još pre 9.000 godina.[16] Male mačke (Felis silvestris) su takođe pripitomljene na ovim prostorima.[17] Takođe, mahunarke uključujući grašak, sočivo i leblebija su domestikovane na ovim prostorima.

Vidi još

urediReference

uredi- ^ Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana; McBride, Bunny (13. 1. 2013). The Essence of Anthropology (3rd izd.). Belmont, California: Cengage Learning. str. 104. ISBN 978-1111833442.

- ^ Ancient Mesopotamia/India. Culver City, California: Social Studies School Service. 2003. str. 4. ISBN 978-1560041665.

- ^ Mezolitske osnove neolitskih kultura u Južnom Pomoravlju, Dragoslav Srejović, Elektronsko izdanje — zajednički poduhvat TIA Janus i Ars Libri, Beograd, 2001, Pristupljeno 15. aprila 2011.

- ^ The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. „Fertile Crescent”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Cambridge University Press. Pristupljeno 28. 1. 2018.

- ^ a b Abt, Jeffrey (2011). American Egyptologist: the life of James Henry Breasted and the creation of his Oriental Institute. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. str. 193—194, 436. ISBN 978-0-226-0011-04.

- ^ Goodspeed, George Stephen (1904). A History of the ancient world: for high schools and academies. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. str. 5–6.

- ^ Breasted, James Henry (1914). „Earliest man, the Orient, Greece, and Rome” (PDF). Ur.: Robinson, James Harvey; Breasted, James Henry; Beard, Charles A. Outlines of European history, Vol. 1. Boston: Ginn. str. 56—57. Arhivirano (PDF) iz originala 2022-10-09. g. "The Ancient Orient" map is inserted between pages 56 and 57.

- ^ Breasted, James Henry (1916). Ancient times, a history of the early world: an introduction to the study of ancient history and the career of early man (PDF). Boston: Ginn. str. 100—101. Arhivirano (PDF) iz originala 2022-10-09. g. "The Ancient Oriental World" map is inserted between pages 100 and 101.

- ^ Clay, Albert T. (1924). „The so-called Fertile Crescent and desert bay”. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 44: 186—201. JSTOR 593554. doi:10.2307/593554.

- ^ Kuklick, Bruce (1996). „Essay on methods and sources”. Puritans in Babylon: the ancient Near East and American intellectual life, 1880–1930. Princeton: Princeton University Press. str. 241. ISBN 978-0-691-02582-7. „Textbooks...The true texts brought all of these strands together, the most important being James Henry Breasted, Ancient Times: A History of the Early World (Boston, 1916), but a predecessor, George Stephen Goodspeed, A History of the Ancient World (New York, 1904), is outstanding. Goodspeed, who taught at Chicago with Breasted, antedated him in the conception of a 'crescent' of civilization.”

- ^ Scheffler, Thomas (2003-06-01). „'Fertile Crescent', 'Orient', 'Middle East': The Changing Mental Maps of Southwest Asia”. European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire. 10 (2): 253—272. ISSN 1350-7486. S2CID 6707201. doi:10.1080/1350748032000140796.

- ^ a b v Diamond, Jared (mart 1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1st izd.). W.W. Norton & Company. str. 480. ISBN 978-0-393-03891-0. OCLC 35792200.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (9. 7. 2009). Basbanes, Nicholas A.; Davis, Donald G., ur. The Library: An Illustrated History. Internet Reference Services Quarterly. 15. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. str. 69—70. ISBN 9781628733228. OCLC 277203534. S2CID 61069680. doi:10.1080/10875300903535149.

- ^ Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction . Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. str. 1082. ISBN 978-0-395-87274-1.

- ^ Norris, Scott (1. 6. 2006). „Ancient Fig Find May Push Back Birth of Agriculture”. National Geographic Society. National Geographic News. Pristupljeno 6. 3. 2017.

- ^ „Genographic Project: The Development of Agriculture”. National Geographic. Pristupljeno 14. 4. 2016.

- ^ Driscoll, Carlos A.; Menotti-Raymond, Marilyn; Roca, Alfred L.; Hupe, Karsten; Johnson, Warren E.; Geffen, Eli; Harley, Eric H.; Delibes, Miguel; Pontier, Dominique; Kitchener, Andrew C.; Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; O'Brien, Stephen J.; Macdonald, David W. (27. 7. 2007). „The near eastern origin of cat domestication”. Science. 317 (5837): 519—523. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..519D. PMC 5612713 . PMID 17600185. doi:10.1126/science.1139518.

Literatura

uredi- Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years, 1997.

- Anderson, Clifford Norman. The Fertile Crescent: Travels In the Footsteps of Ancient Science. 2d ed., rev. Fort Lauderdale: Sylvester Press, 1972.

- Deckers, Katleen. Holocene Landscapes Through Time In the Fertile Crescent. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011.

- Ephʻal, Israel. The Ancient Arabs: Nomads On the Borders of the Fertile Crescent 9th–5th Centuries B.C. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1982.

- Kajzer, Małgorzata, Łukasz Miszk, and Maciej Wacławik. The Land of Fertility I: South-East Mediterranean Since the Bronze Age to the Muslim Conquest. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016.

- Kozłowski, Stefan Karol. The Eastern Wing of the Fertile Crescent: Late Prehistory of Greater Mesopotamian Lithic Industries. Oxford: Archaeopress, 1999.

- Potts, Daniel T. (21. 5. 2012). Potts, D. T, ur. A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. 1. John Wiley & Sons. str. 1445. ISBN 9781405189880. doi:10.1002/9781444360790.

- Steadman, Sharon R.; McMahon, Gregory (15. 9. 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Oxford University Press. str. 1174. ISBN 9780195376142.

- Thomas, Alexander R. The Evolution of the Ancient City: Urban Theory and the Archaeology of the Fertile Crescent. Lanham: Lexington Books/Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

- Cruciani F, La Fratta R, Torroni A, Underhill PA, Scozzari R (avgust 2006). „Molecular dissection of the Y chromosome haplogroup E-M78 (E3b1a): a posteriori evaluation of a microsatellite-network-based approach through six new biallelic markers”. Human Mutation. 27 (8): 831—832. PMID 16835895. S2CID 26886757. doi:10.1002/humu.9445 .

- King RJ, Ozcan SS, Carter T, Kalfoğlu E, Atasoy S, Triantaphyllidis C, et al. (mart 2008). „Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cretan Neolithic”. Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (Pt 2): 205—214. PMID 18269686. S2CID 22406638. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00414.x.

- Shen P, Lavi T, Kivisild T, Chou V, Sengun D, Gefel D, et al. (septembar 2004). „Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence variation”. Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248—260. PMID 15300852. S2CID 1571356. doi:10.1002/humu.20077.

- Zalloua, P., Wells, S. (2004) "Who Were the Phoenicians?" National Geographic Magazine, October 2004.

- Manning, Richard (1. 2. 2005). Against the Grain: How Agriculture Has Hijacked Civilization. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-1-4668-2342-6.

- Civitello, Linda. Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People (Wiley, 2011) excerpt

- Federico, Giovanni. Feeding the World: An Economic History of Agriculture 1800–2000 (Princeton UP, 2005) highly quantitative

- Grew, Raymond. Food in Global History Arhivirano na sajtu Wayback Machine (4. jun 2011) (1999)

- Heiser, Charles B. Seed to Civilization: The Story of Food (W.H. Freeman, 1990)

- Herr, Richard, ed. Themes in Rural History of the Western World (Iowa State UP, 1993)

- Mazoyer, Marcel, and Laurence Roudart. A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis (Monthly Review Press, 2006) Marxist perspective

- Prentice, E. Parmalee. Hunger and History: The Influence of Hunger on Human History (Harper, 1939)

- Tauger, Mark. Agriculture in World History (Routledge, 2008)

- Bakels, C.C. The Western European Loess Belt: Agrarian History, 5300 BC – AD 1000 (Springer, 2009)

- Barker, Graeme, and Candice Goucher, eds. The Cambridge World History: Volume 2, A World with Agriculture, 12000 BCE–500 CE. (Cambridge UP, 2015)

- Bowman, Alan K. and Rogan, Eugene, eds. Agriculture in Egypt: From Pharaonic to Modern Times (Oxford UP, 1999)

- Cohen, M.N. The Food Crisis in Prehistory: Overpopulation and the Origins of Agriculture (Yale UP, 1977)

- Crummey, Donald and Stewart, C.C., eds. Modes of Production in Africa: The Precolonial Era (Sagem 1981)

- Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel (W.W. Norton, 1997)

- Duncan-Jones, Richard. Economy of the Roman Empire (Cambridge UP, 1982)

- Habib, Irfan. Agrarian System of Mughal India (Oxford UP, 3rd ed. 2013)

- Harris, D.R., ed. The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, (Routledge, 1996)

- Isager, Signe and Jens Erik Skydsgaard. Ancient Greek Agriculture: An Introduction (Routledge, 1995)

- Lee, Mabel Ping-hua. The economic history of china: with special reference to agriculture (Columbia University, 1921)

- Murray, Jacqueline. The First European Agriculture (Edinburgh UP, 1970)

- Oka, H-I. Origin of Cultivated Rice (Elsevier, 2012)

- Price, T.D. and A. Gebauer, eds. Last Hunters – First Farmers: New Perspectives on the Prehistoric Transition to Agriculture (1995)

- Srivastava, Vinod Chandra, ed. History of Agriculture in India (5 vols., 2014). From 2000 BC to present.

- Stevens, C.E. "Agriculture and Rural Life in the Later Roman Empire" in Cambridge Economic History of Europe, Vol. I, The Agrarian Life of the Middle Ages (Cambridge UP, 1971)

- Teall, John L. (1959). „The grain supply of the Byzantine Empire, 330–1025”. Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 13: 87—139. JSTOR 1291130. doi:10.2307/1291130.

- Yasuda, Y., ed. The Origins of Pottery and Agriculture (SAB, 2003)

Spoljašnje veze

uredi- Ancient Fertile Crescent Almost Gone, Satellite Images Show– from National Geographic News, May 18, 2001. Arhivirano oktobar 16, 2008 na sajtu Wayback Machine

- http://www.claudiusptolemy.org/AbshireGusevStafeyev_ProceedingsVenice2017.pdf Corey Abshire , Dmitri Gusev , Sergey Stafeyev The Fertile Crescent in Ptolemy’s “Geography”: a new digital reconstruction for modern GIS tools