Ђордано Бруно

Ђордано Бруно (итал. Giordano Bruno; Нола, 1548 — Рим, 17. фебруар 1600), је био италијански филозоф, астроном, и окултист.[1] Погубљен као јеретик, јер су његове идеје биле у супротности за доктрином католичке цркве. Схоластички је образован али ради сумње у традиционално учење бежи из самостана у Женеву, па у Париз. Он прихвата Коперников хелиоцентрични систем. За Ђордана Бруна свемир је бесконачан а природа је Бог у стварима. Преваром је дошао у Венецију где га хапси инквизиција и живог спаљује на ломачи 1600. године. У завршном пасусу пресуде Бруну је писало: „Казнити дакле брата Ђордана благо и без проливања крви“.[2]

| Ђордано Бруно | |

|---|---|

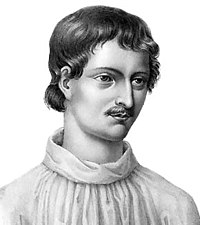

Савремени портрет заснован на дуборезу из „Livre du recteur”, 1578 | |

| Лични подаци | |

| Пуно име | Филипо Бруно |

| Датум рођења | 1548. |

| Место рођења | Нола, Напуљска краљевина |

| Датум смрти | 17. фебруар 1600. (51/52 год.) |

| Место смрти | Рим, Папска држава |

| Филозофски рад | |

| Утицаји од | Ибн Рушд, Никола Коперник, Никола Кузански, Лукреције, Рамон Љуљ, Марсилио Фичино |

Почевши од 1593. године, Римска инквизиција је судила Бруну због јереси под оптужбом порицања неколико основних католичких доктрина, укључујући вечно проклетство, Тројство, Христов божански статус, Маријино девичанство и трансубстанцијацију. Брунов пантеизам црква није олако схватила,[3] нити његово учење о трансмиграцији душе (реинкарнација). Инквизиција га је прогласила кривим и спаљен је на ломачи у римском Кампу де Фиори 1600. године. Након његове смрти, стекао је значајну славу, посебно су га прославили коментатори из 19. и почетка 20. века који су га сматрали мучеником за науку, иако се већина историчара слаже да његово суђење због јереса није одговор на његове космолошке погледе, већ одговор на његова верска и загробна гледишта.[4][5][6][7][8] Међутим, неки историчари[9] тврде да су главни разлог Брунове смрти заиста били његови космолошки погледи. Брунов случај се и даље сматра оријентиром у историји слободног мишљења и наукама у настајању.[10][11]

Осим космологије, Бруно је опширно писао и о уметности памћења, лабаво организованој групи мнемоничких техника и принципа. Историчар Франсес Јејтс тврди да је Бруно био под великим утицајем исламске астрологије (посебно филозофије Авероеса[12]), неоплатонизма, ренесансног херметизма и легенди сличних Постанку које окружују египатског бога Теута.[13] Друге Брунове студије фокусирале су се на његов квалитативни приступ математици и његову примену просторних концепата геометрије на језик.[14]

Лист "Авази ди Рома" писао је о погубљењу Бруна: "Доминиканац из Ноле који изазива гнушање, жив је спаљен на Кампо де Фјори. Био је непоправљив јеретик који је ширио догму против наше вере, а нарочито против Богородице и других Светаца. Тај бедник је толико био упоран у својој вери да је био спреман да за њу умре. Рекао је да радо умире као мученик, јер ће његова душа кроз пламен да оде у Рај."

Најпотпунија књига на српском језику о животу, делу и страдању Ђордана Бруна са хронологијом и библиографијом је: Александра Манчић: Ђордано Бруно и комуникација. Превођење идеја, Службени гласник. . Београд. 2015. ISBN 978-86-519-1941-4., књига је добила награду Никола Милошевић за 2015. годину, за најбољу књигу у области филозофије, есејистике и теорије књижевности и уметности.

Види још уреди

Референце уреди

- ^ Gatti, Hilary (2002). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-801-48785-4.

- ^ Mirko Đorđević, Eppur si muove Архивирано на сајту Wayback Machine (19. септембар 2009), Приступљено 4. 5. 2013.

- ^ Birx, H. James. "Giordano Bruno" Архивирано на сајту Wayback Machine (16. мај 2019) The Harbinger, Mobile, AL, 11 November 1997. "Bruno was burned to death at the stake for his pantheistic stance and cosmic perspective."

- ^ Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964, p. 450

- ^ Michael J. Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750–1900, Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 10, "[Bruno's] sources... seem to have been more numerous than his followers, at least until the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century revival of interest in Bruno as a supposed 'martyr for science.' It is true that he was burned at the stake in Rome in 1600, but the church authorities guilty of this action were almost certainly more distressed at his denial of Christ's divinity and alleged diabolism than at his cosmological doctrines."

- ^ Adam Frank (2009). The Constant Fire: Beyond the Science vs. Religion Debate, University of California Press, p. 24, "Though Bruno may have been a brilliant thinker whose work stands as a bridge between ancient and modern thought, his persecution cannot be seen solely in light of the war between science and religion."

- ^ White, Michael (2002). The Pope and the Heretic: The True Story of Giordano Bruno, the Man who Dared to Defy the Roman Inquisition, p. 7. Perennial, New York. "This was perhaps the most dangerous notion of all... If other worlds existed with intelligent beings living there, did they too have their visitations? The idea was quite unthinkable."

- ^ Shackelford, Joel (2009). „Myth 7 That Giordano Bruno was the first martyr of modern science”. Ур.: Numbers, Ronald L. Galileo goes to jail and other myths about science and religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. стр. 66. "Yet the fact remains that cosmological matters, notably the plurality of worlds, were an identifiable concern all along and appear in the summary document: Bruno was repeatedly questioned on these matters, and he apparently refused to recant them at the end.14 So, Bruno probably was burned alive for resolutely maintaining a series of heresies, among which his teaching of the plurality of worlds was prominent but by no means singular."

- ^ Martínez, Alberto A. (2018). Burned Alive: Giordano Bruno, Galileo and the Inquisition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-1780238968.

- ^ Gatti, Hilary (2002). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. стр. 18—19. ISBN 978-0801487859. Приступљено 21. 3. 2014. „For Bruno was claiming for the philosopher a principle of free thought and inquiry which implied an entirely new concept of authority: that of the individual intellect in its serious and continuing pursuit of an autonomous inquiry… It is impossible to understand the issue involved and to evaluate justly the stand made by Bruno with his life without appreciating the question of free thought and liberty of expression. His insistence on placing this issue at the center of both his work and of his defense is why Bruno remains so much a figure of the modern world. If there is, as many have argued, an intrinsic link between science and liberty of inquiry, then Bruno was among those who guaranteed the future of the newly emerging sciences, as well as claiming in wider terms a general principle of free thought and expression.”

- ^ Montano, Aniello (2007). Antonio Gargano, ур. Le deposizioni davanti al tribunale dell'Inquisizione. Napoli: La Città del Sole. стр. 71. „In Rome, Bruno was imprisoned for seven years and subjected to a difficult trial that analyzed, minutely, all his philosophical ideas. Bruno, who in Venice had been willing to recant some theses, became increasingly resolute and declared on 21 December 1599 that he 'did not wish to repent of having too little to repent, and in fact did not know what to repent.' Declared an unrepentant heretic and excommunicated, he was burned alive in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome on Ash Wednesday, 17 February 1600. On the stake, along with Bruno, burned the hopes of many, including philosophers and scientists of good faith like Galileo, who thought they could reconcile religious faith and scientific research, while belonging to an ecclesiastical organization declaring itself to be the custodian of absolute truth and maintaining a cultural militancy requiring continual commitment and suspicion.”

- ^ „Giordano Bruno”. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ The primary work on the relationship between Bruno and Hermeticism is Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and The Hermetic Tradition, 1964; for an alternative assessment, placing more emphasis on the Kabbalah, and less on Hermeticism, see Karen Silvia De Leon-Jones, Giordano Bruno and the Kabbalah, Yale, 1997; for a return to emphasis on Bruno's role in the development of Science, and criticism of Yates' emphasis on magical and Hermetic themes, see Hillary Gatti (1999), Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science, Cornell.

- ^ Alessandro G. Farinella and Carole Preston, "Giordano Bruno: Neoplatonism and the Wheel of Memory in the 'De Umbris Idearum'", in Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 2, (Summer, 2002), pp. 596–624; Arielle Saiber, Giordano Bruno and the Geometry of Language, Ashgate, 2005

Литература уреди

- Blackwell, Richard J.; de Lucca, Robert (1998). Cause, Principle and Unity: And Essays on Magic by Giordano Bruno. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59658-9.

- Blum, Paul Richard (1999). Giordano Bruno. Munich: Beck Verlag. ISBN 978-3-406-41951-5.

- Blum, Paul Richard (2012). Giordano Bruno: An Introduction. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-3555-3.

- Bombassaro, Luiz Carlos (2002). Im Schatten der Diana. Die Jagdmetapher im Werk von Giordano Bruno. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag.

- Culianu, Ioan P. (1987). Eros and Magic in the Renaissance. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-12315-8.

- Aquilecchia, Giovanni; montano, aniello; bertrando, spaventa (2007). Gargano, Antonio, ур. Le deposizioni davanti al tribunale dell'Inquisizione. La Citta del Sol.

- Gatti, Hilary (2002). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8785-9.

- Kessler, John (1900). Giordano Bruno: The Forgotten Philosopher. Rationalist Association.

- McIntyre, J. Lewis (1997). Giordano Bruno. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56459-141-8.

- Mendoza, Ramon G. (1995). The Acentric Labyrinth. Giordano Bruno's Prelude to Contemporary Cosmology. Element Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85230-640-3.

- Rowland, Ingrid D. (2008). Giordano Bruno: Philosopher/Heretic. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-8090-9524-7.

- Saiber, Arielle (2005). Giordano Bruno and the Geometry of Language. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3321-1.

- Singer, Dorothea (1950). Giordano Bruno: His Life and Thought, With Annotated Translation of His Work – On the Infinite Universe and Worlds. Schuman. ISBN 978-1-117-31419-8.

- White, Michael (2002). The Pope & the Heretic . New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-018626-5.

- Yates, Frances (1964). Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-95007-5.

- Michel, Paul Henri (1962). The Cosmology of Giordano Bruno. Превод: R.E.W. Maddison. Paris/London/Ithaca, New York: Hermann/Methuen/Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0509-2.

- Bruno, Giordano (2002). The Cabala of Pegasus. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09217-2.

- Giordano Bruno, Paul Oskar Kristeller, Collier's Encyclopedia, Vol 4, 1987 ed., p. 634

- Il processo di Giordano Bruno, Luigi Firpo, 1993

- Giordano Bruno,Il primo libro della Clavis Magna, ovvero, Il trattato sull'intelligenza artificiale, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore.

- Giordano Bruno,Il secondo libro della Clavis Magna, ovvero, Il Sigillo dei Sigilli, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore.

- Giordano Bruno, Il terzo libro della Clavis Magna, ovvero, La logica per immagini, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

- Giordano Bruno, Il quarto libro della Clavis Magna, ovvero, L'arte di inventare con Trenta Statue, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

- Giordano Bruno L'incantesimo di Circe, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

- Guido del Giudice, WWW Giordano Bruno, Marotta & Cafiero Editori. Giudice, Guido Del (2001). WWW.Giordano Bruno. Marotta e Cafiero. ISBN 88-88234-01-2.

- Giordano Bruno, De Umbris Idearum, a cura di Claudio D'Antonio, Di Renzo Editore

- Guido del Giudice, La coincidenza degli opposti, Di Renzo Editore. ISBN 88-8323-110-4, 2005 (seconda edizione accresciuta con il saggio Bruno, Rabelais e Apollonio di Tiana, Di Renzo Editore, Roma. Giudice, Guido Del (2006). La coincidenza degli opposti: Giordano Bruno tra Oriente e Occidente. Di Renzo Editore. ISBN 88-8323-148-1.)

- Giordano Bruno, Due Orazioni: Oratio Valedictoria – Oratio Consolatoria, a cura di Guido del Giudice, Di Renzo Editore. Bruno, Giordano (2007). Due orazioni. Di Renzo. ISBN 978-88-8323-174-2.

- Giordano Bruno, La disputa di Cambrai. Camoeracensis Acrotismus, a cura di Guido del Giudice, Di Renzo Editore. Bruno, Giordano (2008). La disputa di Cambrai. Di Renzo. ISBN 978-88-8323-199-5.

- Somma dei termini metafisici, a cura di Guido del Giudice, Di Renzo Editore, Roma, 2010

- Massimo Colella, "'Luce esterna (Mitra) e interna (G. Bruno)'. Il viaggio bruniano di Aby Warburg", in «Intersezioni. Rivista di storia delle idee», XL, 1, 2020, pp. 33–56.

Додатна литература уреди

- Dilwyn Knox (2019). Giordano Bruno. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Спољашње везе уреди

- Ђордано Бруно: есеј Р. Г. Ингерсола

- Paul Richard Blum (2021). Giordano Bruno. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- How 'Cosmos' Bungles the History of Religion and Science

- Bruno's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Writings of Giordano Bruno

- Giordano Bruno Library of the World's Best Literature Ancient and Modern Charles Dudley Warner Editor

- Bruno's Latin and Italian works online: Biblioteca Ideale di Giordano Bruno

- Complete works of Bruno as well as main biographies and studies available for free download in PDF format from the Warburg Institute and the Centro Internazionale di Studi Bruniani Giovanni Aquilecchia

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Giordano Bruno in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Giordano Bruno на сајту Пројекат Гутенберг (језик: енглески)

- Ђордано Бруно на сајту LibriVox (језик: енглески)

- Ђордано Бруно на сајту Internet Archive (језик: енглески)